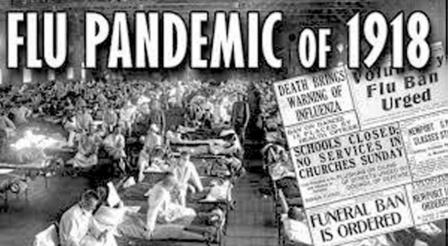

Spanish Flu: 1918-1920

I have been inspired to share this story now because, at the time of writing, the world is in the grips of another pandemic: Coronavirus (Covid 19). In UK, we are in lock-down and there seems to be no end anytime soon. The fact that much of the world was suffering from similar circumstances a century ago is somehow ironic.

Despite the name Spanish Flu, it is likely the disease did not start in Spain. Spain had been a neutral nation during the First World War and had not enforced strict censorship of its press which could, therefore, freely publish early accounts of the illness. As a result, people falsely believed the illness was specific to Spain, and the name Spanish Flu stuck. One of the first casualties was, in fact, the King of Spain.

During the pandemic, an estimated 500 million people from the South Seas to the North Pole fell victim to Spanish Flu. The death toll is estimated to have been anywhere from 17 million to 50 million, and possibly as high as 100 million, making it one of the deadliest pandemics in human history, with some indigenous communities pushed to the brink of extinction. A quarter of the British population were affected where the death toll rose to 228,000.

Although not caused by World War One, it is thought that in Britain, the virus was spread by soldiers returning home from the trenches in northern France. Soldiers were becoming ill with what was known as ‘la grippe’, the symptoms of which were sore throats, headaches and a loss of appetite. Although highly infectious in the cramped, primitive conditions of the trenches, recovery was usually swift and doctors at first called it “three-day fever”.

However, the outbreak of Spanish Flu hit Britain and it came in a series of waves, with its peak at the end of WW1. Returning from Northern France at the end of the war, the troops travelled home by train. As they arrived at their destinations, so the flu spread from the railway stations to the centre of the cities, then to the suburbs and out into the countryside. The flu’s spread and lethal nature had been enhanced both by the cramped conditions of the soldiers and by the poor nutrition that many people had experienced during wartime. Not restricted to class, anyone could catch it.

My family was not immune.

A great-great uncle of mine, Arthur Lucas, was the brother of my mother’s paternal grandfather Charles Lucas. As a child, I knew Uncle Arthur. He, in fact, came to stay with us at 2 Newton Road, Bitterne Park, Southampton, in the house where I spent the first nine years of my life. I remember he put one of his clean handkerchiefs over the pillow, before he laid his head to rest at night, in order to prevent his hair cream from staining the pillowcase. How thoughtful!

I knew that his wife, Aunt Jess, was his second wife. I had been told his first wife had died young leaving Arthur with a 5 or 6 year-old son to look after. The story went that, when he married Jess, she readily accepted the little boy and brought him up as her child. She and Arthur had no children of their own.

Being an avid family historian, I decided to look into this story and try to find out more. This is what I learned…

Son of an RSPCA Inspector, Arthur was born on 27th July 1885 in Eastbourne but, by the age of 15 years, he and the family were living in Macclesfield, Cheshire. He had a job as a miller’s clerk. On 30th April 1910, he married Ethel Hazlehurst at the Church of St John the Evangelist, in the parish of Altrincham, Ethel’s home. He was coming up 25 years old and Ethel was about 20. They soon moved to Harrow in Middlesex where they appear on the 1911 census, with Arthur recorded as a book-keeper. It appears, however, that they returned to Cheshire fairly quickly as their sons were both born there, John Arthur (always known to the family as “Young Arthur”) in 1912 and Charles Alan in 1916. Arthur was then working as an Engineer’s Clerk.

Tragically, only six years into the marriage, Ethel, aged just 27 years, and their 2-year old son both died on the same day leaving him with his 6 year-old son, Young Arthur. Ethel and Charles died during the great ‘flu epidemic which was sweeping Northern Europe at the time. They had both contracted influenza, which led to pneumonia and consequently death.

Sadder still, is the fact that Arthur’s surviving son was never truly healthy and suffered from respiratory problems throughout his life. He died relatively young in 1951, at The Cranford Lodge Hospital, Knutsford, in Cheshire. He was just 39 years old, his father outliving him by seven years.

“I had a little bird

its name was Enza

I opened the window,

And in-flu-enza.”

(1918 children’s playground rhyme)

Kay Lovell